The song of Banaras

A novella by Kiran Khalap

after the movie, “Banaras, A Mystic Love Story”

Shwetambari, Anita, Mauritius, Now:

Sea and Wave, Water and River

The wave rises on its hind legs, unsheathes its white claws, pauses before pouncing.

The rocks hunker and brace themselves, dig their feet deeper into the sand, draw a deep breath.

Then the attack: The water rushes into the crannies of the rocks, enters their nostrils, smothers them, growling and hissing.

Wave and sea, sea and wave.

Two words, same thing.

There was water in Banaras too.

But no waves.

Just a tranquil liquid languid wall, gliding towards the sea.

Water and river, river and water.

Two words, same thing.

I stand there on the cliff overlooking the sea, on the brink of the second biggest decision of my life.

I walked away from the man I respected the most in my life, now he is on deathbed, crying out for me to return before he slips away from everybody.

I had felt his anguish even before they informed me of the phone call.

Inside an hour, the quiet river of consciousness within me has been transformed into a broiling sea.

“Didi,” it’s Anita, standing behind the translucent petals of the curtains.

Anita, my shadow, my friend, my secretary for the past decade.

“Yes?”

“If you don’t mind my asking, Didi…” Always tentative, not wanting to intrude even on territory that’s rightfully hers.

“Didi…you ended the meditation session abruptly, you didn’t have your evening soup, you haven’t gone to sleep…I am worried…”

“How does one worry about what is inevitable, Anita?”

“I don’t understand, Didi…”

“For that, Anita, we have to return to the beginning…to a man called Soham, who died…to another called Babaji, who apparently never dies…to a mystery called Banaras.”

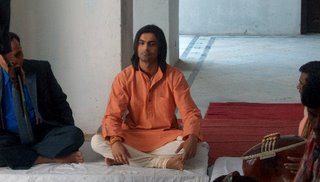

Sohan aka Soham, Banaras, Past.

On the tips of a trident

In the beginning was a city called Banaras.

Balanced on the tip of Lord Shiva’s trident, balanced between history and mythology.

The only city on the left bank of the mighty river Ganges, the only city facing the East, opening its eyes, every morning, to two suns.

One in the sky, one in the river.

I imagine that the stone steps that led to the river must have been cold at dawn. Daadima told me I was wrapped up in a blanket, the unwanted son of…who?

All my life, as I grow up, I made up stories about my mother to myself.

Who was she?

A young unmarried woman seduced by a local rake?

A farmhand who had been called upon to warm the bed of the drunken landlord?

A careless prostitute?

And what about my father?

A rich Brahmin who couldn’t convince his parents to get him married to a low-caste girl, the girl he said he loved?

A powerful politician, who miscalculated the tenacity of his mistress?

Whoever she was, my mother had placed a good luck charm around my neck, a metal Om.

That’s who I was.

A bawling baby armed with the first sound in the universe. Armed to take on whatever fate had in store for me.

Daadima adopted me and named me Sohan.

This is the way I climbed up a ladder.

From being an illegitimate child to being the adopted child of a low-caste sweeper woman.

One humiliating rung at a time.

Daadima insisted I join school. “Learn to read and write, my baby, it can change your life”.

I remember her rough hand, rough with so many years of holding the broom and sweeping the streets, on my back, as I buried my tears in her embrace after the first day.

“Your highness Mr Sohan, stand up on that last bench. Now tell me why do you want to sit here instead of being out there keeping our lanes clean, that’s your job, isn’t it?” the teacher had said. He was a thin man with thick spectacles, always in a crisp white dhoti and kurta. When he spoke, saliva as foam collected at the corners of his mouth.

One boy sniggered. Another tried to look up my shorts.

“He’s all dirty and unwashed, like all sweepers’!”

I was staring at my toes. My ears were burning.

“What happened, your mother told you not to speak to us high caste people?”

“Doesn’t have a mother…or father!” giggled a third boy.

“Sir, I just want to learn to read and write.” It’s difficult to speak when you actually want to sob.

“And do what…teach Brahmin boys how to do pooja, is it? Come here, let me remind you that you were born to hold a broom and not a pen.”

The cane whipping made my palms bleed. I could not make out what hurt more, the welts on the palm or inside my head.

“Daadima, if I had a big strong father, he would not be afraid. He would have gone and spoken to the teacher… and then the boys wouldn’t tease, and then when I learn to read…”

I slipped into sleep, dreaming of a father with a curled moustache and big muscles, clutching my tormentor by his neck, while I sit giggling, drawing a sketch with my pen, a man holding a squawking chicken.